Dear Diary,

Fourth year clinical rotations are the pinnacle of optometry school that all students are anxious for. It’s a time of freedom, learning, and exposure to parts of optometry you may never see in the school clinic. Or is it?

My name is Lawrence Yu, and I’ve started my clinical rotations as a fourth year student at the Southern California College of Optometry at Marshall B. Ketchum University. Through this blog, I will chronicle and share my rotations experience throughout the year at my four different sites. Join me as I leave the safety of the school clinic and enter the real world of optometry. Learn with me as I see some crazy eye diseases. Suffer with me as I endure moving every 2.5 months. Follow me and prepare yourself for your last year of optometry school.

—–

Lessons from the First Rotation: Day 79 of 79 at Naval Medical Center of San Diego

“I picked this as my first rotation because military sites have reputations for speed and efficiency, and I wanted to become fast to start my year off.” – my slower self 2.5 months ago

Speed was the name of the game throughout my first quarter of clinical rotations. I hoped to become a faster clinician to start my fourth year, and I have definitely pumped up my optometric engine after training for one quarter. Regardless of the kind of modality you practice in for your first rotation, you will inherently become faster from giving eye exams every day.

Here are some things that I recommend for fine tuning your optometric engine for even more speed:

-

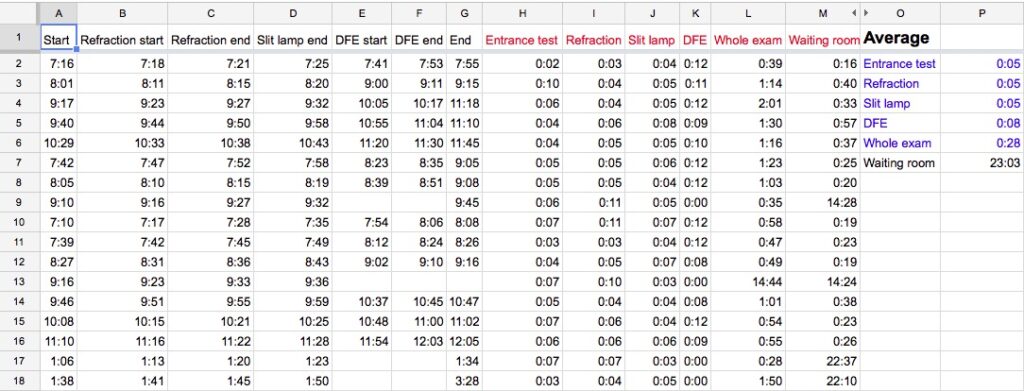

Improvement is in the numbers. Keep track of your exam times to monitor what procedures are slowing you down and where you can improve. Here’s an example of a spreadsheet I had open during my exams:

After tracking my average exam times, I found specific things about my eye exams that I never would’ve noticed subjectively. For example, I hadn’t noticed that my DFE took longer than I’d prefer because of my concentration while scanning the peripheral retina. The exam times also told me that case history/entrance testing was taking too long, so I learned to focus my questions to promote more prompt answers. -

Chart during the exam, not after. My rotation site had enough patients to allow me to juggle two to three patients at once, and it was extremely easy to forget my findings with my brain split amongst three patients. There were certain points of dead time in my exams where I could chart without disruption in flow, such as after refraction or after administering Fluress while the patient was getting used to the drop. Chart during these empty moments in your exam, and save yourself from the time drain and mental drain of charting after the patient leaves.

-

Know when to give up and try something else. In optometry school, you learn many different methods to assess the same thing. If you’re struggling to assess the health of an undilated eye with slit lamp and 90D, don’t spend too much time struggling. Simply go straight for your direct ophthalmoscope and continue on. There are many different ways to measure phorias in case one does not work.

Overall, here are a few important lessons learned from my first rotation (scroll all the way down for some interesting photos):

Throughout my first rotation, I learned to never assume that a patient will be healthy and an easy eye exam. With a young and healthy population base, the military hospital was not a very extensive disease experience. Military personnel are expected to maintain good health and tend to retire in their early 40s. However, I was always surprised by the retinal holes, keratoconus, and glaucoma suspects that I found in unassuming young men and women. Keep your eyes open and don’t slack off in your optometric care just because your healthy 25 year old patient has no entering complaints. You never know what you may find.

Another big lesson from my first rotation was learning to deliver effective patient education. From my experience, success in delivering meaningful patient care is 10% diagnosis with treatment and 90% patient education. The easy part of the exam was finding the disease or condition requiring treatment; the hard part was explaining the situation to the patient. My patients had preconceived notions that good vision meant good eye health, and I had a difficult time initially educating the patient that preserving eye health meant good vision. With experience, I developed succinct explanations for various ocular conditions that required treatment. Practice your patient education and imagine if your patient would be convinced or not.

Remember to plan your clinical rotation with a meaningful order to develop your optometric skills. I’m extremely happy with having a military site as my first rotation because it developed my speed that can be carried over for my future rotations. It was not extremely disease heavy, so I started off easy to get my optometric feet wet. With a strong foundation, now I can move on to specialties in optometry.